Read the stimuli following the questions below carefully. Then read the sample answers along with expert commentary given below. Happy learning!

This question has three parts: Part A, Part B, and Part C. Use the three sources provided to answer all parts of the question.

For Part B and Part C, you must cite the source that you used to answer the question. You can do this in two different ways:

Parenthetical Citation: For example: “…(Source 1).”

Embedded Citation: For example: “According to Source 1…”

Write the response to each part of the question in complete sentences. Use appropriate psychological terminology.

2. Using the sources provided, develop and justify an argument about the extent to which the limbic system governs human emotional and social behavior.

A. Propose a specific and defensible claim based in psychological science that responds to the question.

B.i. Support your claim using at least one piece of specific and relevant evidence from one of the sources.

ii. Explain how the evidence from Part B (i) supports your claim using a psychological perspective, theory, concept, or research finding learned in AP Psychology.

C.i. Support your claim using an additional piece of specific and relevant evidence from a different source than the one that was used in Part B (i).

ii. Explain how the evidence from Part C (i) supports your claim using a different psychological perspective, theory, concept, or research finding learned in AP Psychology than the one that was used in Part B (ii).

Source 1

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical neurodevelopmental period characterized by significant maturation within the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus. These structures are central to emotional processing and fear memory, respectively. While their individual roles are well-documented, the development of the neural circuitry between them is less understood. This longitudinal study tracked the development of amygdala-hippocampus functional connectivity and its correlation with the emergence of anxiety symptoms over a four-year period in a cohort of typically developing adolescents.

Participants

The study recruited 150 participants (75 female, 75 male) at age 12 (M = 12.1 years, SD = 0.5) from a community sample. Participants were screened for any pre-existing neurological or psychiatric conditions. Retention rate over the four-year study was 92%, with 138 participants completing the final assessment at age 16.

Method

Participants underwent annual functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scans while at rest (resting-state fMRI) to measure intrinsic functional connectivity. Immediately following each scan, participants completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale, a validated self-report measure of anxiety symptom severity. The primary analysis focused on the correlation strength (functional connectivity) between the bilateral amygdala and the bilateral hippocampus.

Results and Discussion

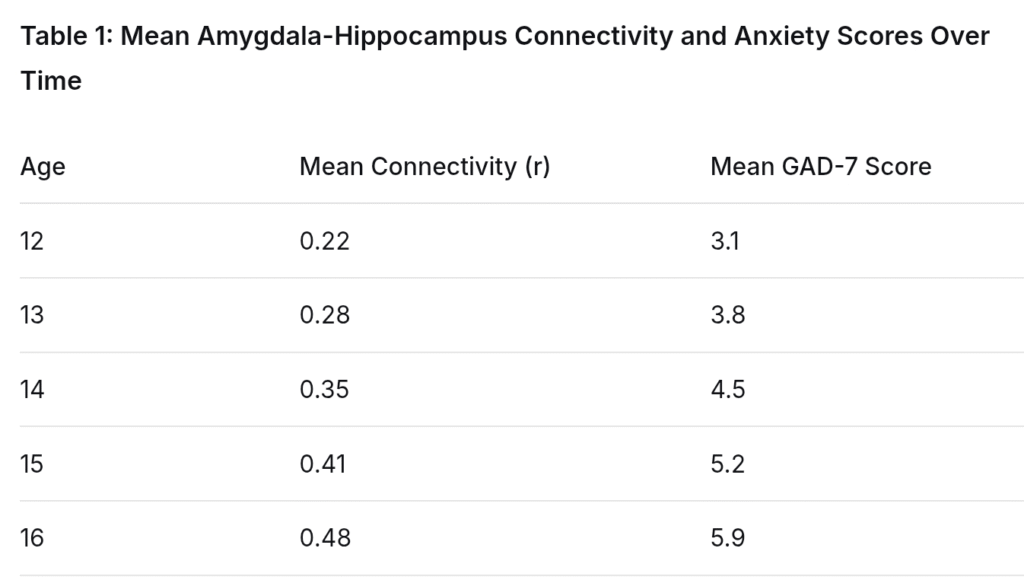

The longitudinal data revealed a clear developmental trend. Amygdala-hippocampus connectivity strengthened significantly from age 12 to 16. Crucially, individual differences in this trajectory were predictive of anxiety outcomes. Participants who showed a steeper-than-average increase in connectivity reported higher levels of anxiety symptoms by age 16. The data table below illustrates the mean connectivity strength (represented by correlation coefficient, r) and mean GAD-7 scores across the study period.

Chen, L., & Hayes, M. P. (2021). A longitudinal fMRI investigation of amygdala-hippocampus connectivity and its relationship to anxiety trajectories in adolescents. Journal of Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 52, 101012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2021.101012

Source 2

Introduction

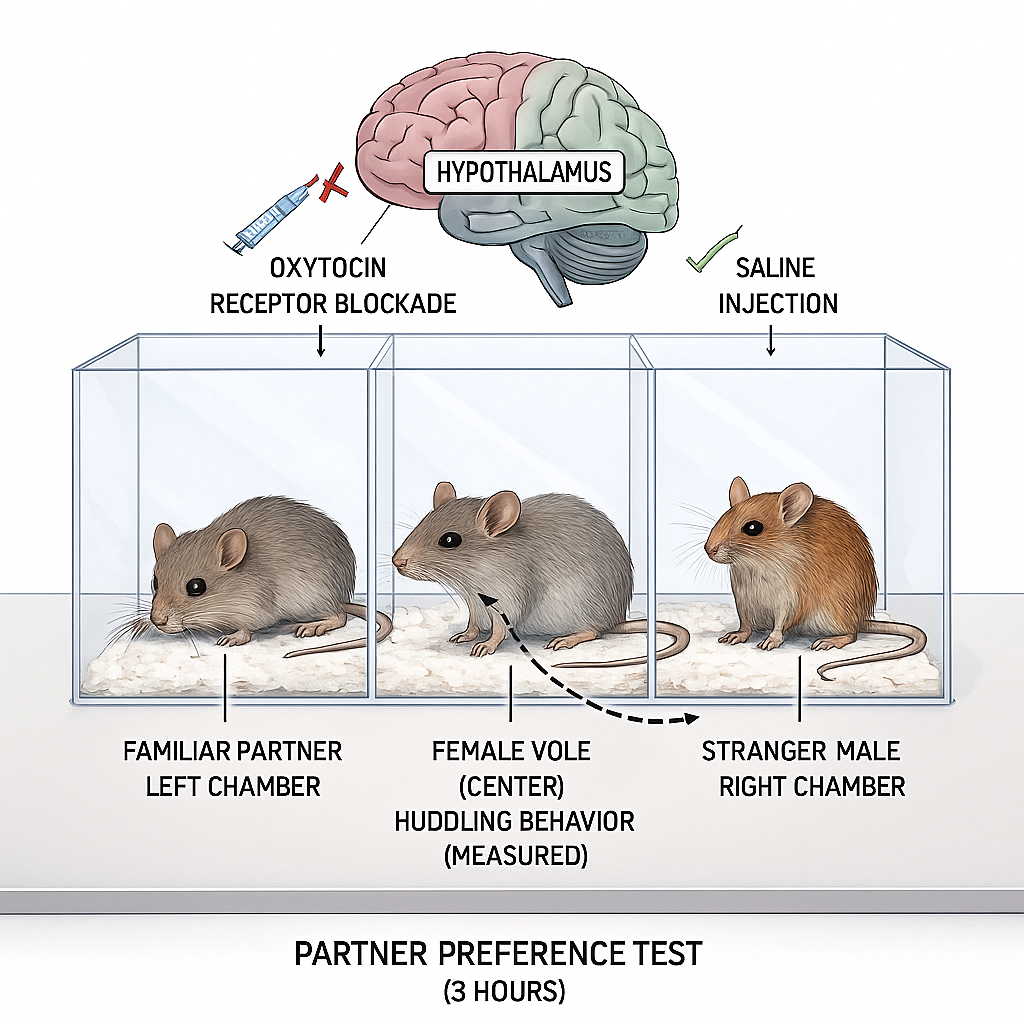

The limbic system is crucial for social behavior. The hypothalamus, a key part of this system, produces and responds to oxytocin, a hormone linked to love and bonding. This study used prairie voles, small rodents known for forming lifelong monogamous pairs, to test if oxytocin in the hypothalamus is necessary for forming a preference for a specific partner.

Participant

The study used 80 adult female prairie voles that had no prior mating or long-term social experience (they were sexually naive). They were divided into two groups of 40.

Method

Each vole spent 24 hours with a male vole to become familiar with him. Then, the experimental group received an injection into the hypothalamus that blocked oxytocin receptors (the parts of the brain that allow oxytocin to work). The control group received a harmless saline injection in the same brain area. After recovery, each female was placed in a three-chamber cage for a 3-hour “partner preference test.” Her familiar partner was tethered in one chamber, and an unfamiliar, stranger male vole was tethered in another.

Researchers measured the percentage of time the female spent huddling side-by-side with each male, which is a sign of social bonding in voles.

Results and Discussion

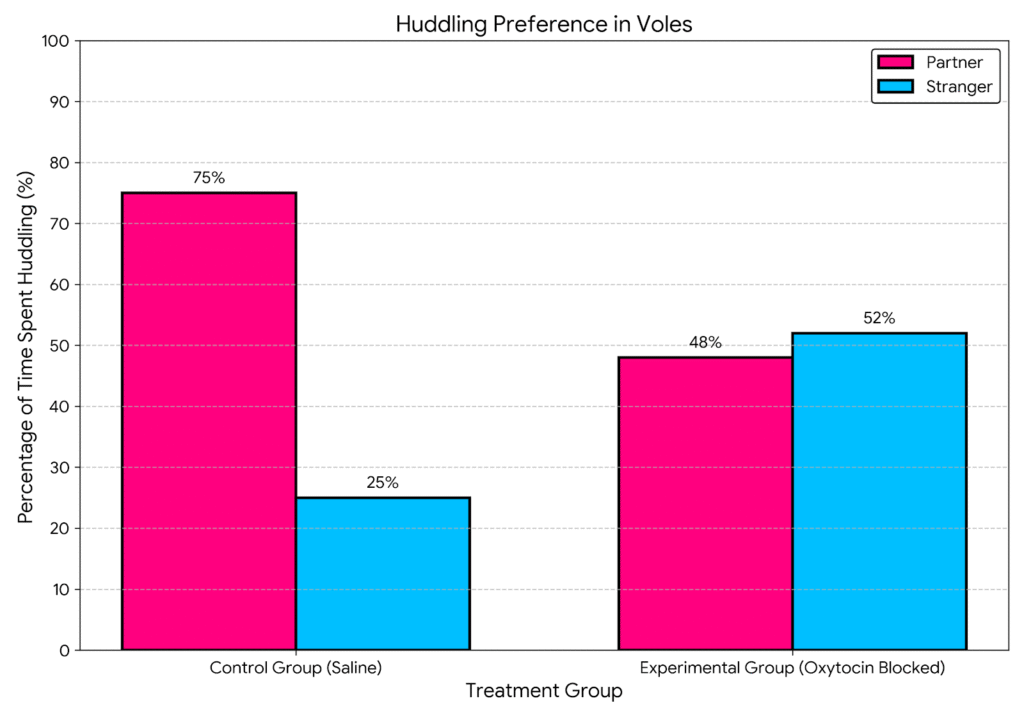

The results were clear. Voles in the control group, who received the saline injection, showed a strong preference for their partner. In contrast, the voles that had their oxytocin receptors blocked showed no preference, spending equal time with the partner and the stranger. The results can be seen in the graph below-

Rivera, S., & Feldman, R. L. (2022). The role of the hypothalamus in social bonding: A study of prairie voles. Behavioral Neuroscience, 136(3), 245-255. https://doi.org/10.1037/bne0000514

Source 3

Introduction

Sometimes, the best way to understand how a brain region works is to see what happens when it is damaged. This report from a national health institute summarizes the behavioral patterns observed in patients with injuries to different parts of the limbic system. By looking at these clinical cases, we can create a direct link between specific limbic structures and the emotions and behaviors they control.

Methodology

The report reviewed the medical files of 200 patients with confirmed damage to one of three limbic system areas: the amygdala, the hippocampus, or the cingulate gyrus. The damage was caused by strokes, tumors, or surgery. For each patient, neurologists and psychologists documented the primary changes in their behavior and emotional responses.

Results and Discussion

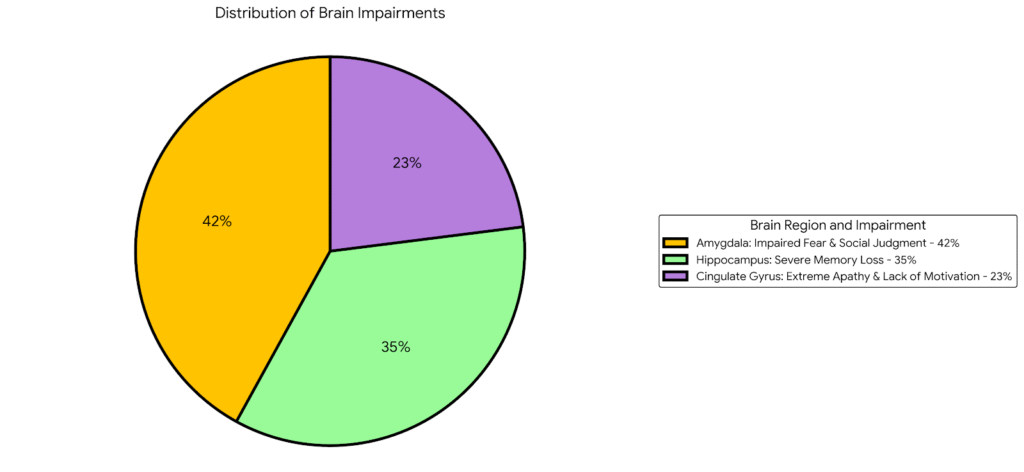

Amygdala Damage: Patients with amygdala damage had great difficulty recognizing fear in other people’s faces and often showed a lack of fear in situations that would normally scare most people. They also often displayed poor social judgment, trusting strangers too easily.

Hippocampus Damage: The most common problem for these patients was severe memory loss, specifically the inability to form new conscious memories (anterograde amnesia). Their old memories and intelligence often remained intact, but they could not remember new people or events for more than a few minutes.

Cingulate Gyrus Damage: Damage here often led to a profound loss of motivation and emotion. Patients became extremely apathetic, showing little interest in speaking, moving, or engaging with others, even though they were physically able to.

The chart below shows the breakdown of the most common type of behavioral impairment documented for patients with damage to each of the three key limbic structures.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). (2023). Clinical case profiles: Behavioral changes from limbic system damage. Clinical Neurology Report, 41(2), 88-95. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuro.23010034

(Note: The created source texts are fictionalized and condensed version inspired by the paradigms and findings of limbic system growth, damage and related studies in the field.)

| Questions and Answers | Commentary |

| Part A: Propose a specific and defensible claim. “The limbic system is the main driver of our most basic emotional and social behaviors. Structures within the limbic system, like the amygdala and hypothalamus, have specific jobs that control things like fear, memory, and social attachment, showing that this brain network is essential for how we feel and interact with others.” | This is a strong, defensible claim. It is specific (“main driver,” “basic emotional and social behaviors”), defensible (it can be supported with evidence from the sources), and rooted in psychological science (it names specific brain structures and their functions). It directly responds to the prompt’s core issue. |

| Part B (i): Support your claim with evidence from a source. “In Source 2, when researchers blocked oxytocin in the hypothalamus of the voles, they didn’t show a partner preference anymore and spent equal time with a stranger (Source 2).” | This is effective evidence. The student provides a specific and relevant piece of data from the source (the result of the oxytocin blockade). The citation is correctly and clearly done. |

| Part B (ii): Explain with a psychological concept. “This supports my claim because it shows the role of the limbic system in social behavior through the concept of neurotransmitters. Oxytocin is a neurotransmitter that works in the limbic system. The study proves that this specific chemical in this specific brain part is what causes the social bonding behavior. Without it, the bond doesn’t form, showing that the limbic system is in charge.” | This is a clear and accurate explanation. The student correctly identifies a key AP Psychology concept (neurotransmitters). The explanation logically connects the evidence (blocking oxytocin) to the concept and then back to the claim (showing the limbic system is “in charge”). |

| Part C (i): Support your claim with evidence from a different source. “Source 3 shows that damage to different limbic structures causes specific problems. For example, 42% of the cases showed that amygdala damage led to problems with feeling fear and social judgment (Source 3).” | This successfully uses a different source (Source 3). The student provides specific evidence (the 42% statistic linked to amygdala damage) and correctly uses a parenthetical citation. This meets the requirement to use a new source. |

| Part C (ii): Explain with a different psychological concept. “This supports my claim by using the idea of localization of function, which is different from neurotransmitters. Localization means that different parts of the brain have different jobs. The fact that damaging the amygdala always messes up fear, and damaging the hippocampus always messes up memory, proves that these behaviors are localized in and controlled by the limbic system.” | This is an excellent application of a second, distinct concept. The student correctly identifies localization of function and explains it in their own words. The explanation powerfully links the clinical evidence from Source 3 to the concept, showing how it proves the limbic system’s primary role. The student explicitly states it is different from the concept used in Part B. |

ap psychology, ap psych, ebq, frq, latest syllabus, 2025-26, 2025, 2026, new frqs, revision, model answers, practice, stimulus, past Paper answers, limbic system, neurotransmitters, biological module, amygdala, neurotransmitters